A sermon preached at St. Philip’s Episcopal Church on Proper 23 Sunday October 13. I reference the spiritual known as A City Called Heaven or Poor Pilgrim of Sorrow. Frank Ward’s homepage including audio of his singing can be found here.

A sermon preached at St. Philip’s Episcopal Church on Proper 23 Sunday October 13. I reference the spiritual known as A City Called Heaven or Poor Pilgrim of Sorrow. Frank Ward’s homepage including audio of his singing can be found here.

A sermon discussing the interpretive principles of the fourth century desert father Evagrius and the twentieth century theologian Howard Thurman.

The following sermon was preached on September 15th of this year. This week marked the anniversary of 9/11 and the Feast day of Harry Thacker Burleigh, the greatest African-American composer and arranger of the black spiritual tradition. This Sunday also marks the Feast of Our Lady of Sorrows in the Roman Catholic tradition and who is celebrated within the black spiritual Weeping Mary sung most famously by Paul Robeson. In our worship, we looked forward in hope and joy with Mavis Staples, our nations finest singer of both gospel and soul from within the black church tradition. Her arrival for a concert in Cleveland this week gave us added encouragement to find our joy even within what she and her beloved father Pops Staples call ‘the heavy.” Sha la boom boom yeah!

Sister Mavis shows us the face of one steeped in joy and intimate with sorrow. As we say in the church, the icon of the face of Christ and his Mother Mary.

(Apologies for the poor sound quality. I preach on the floor, not the pulpit and the microphone is not as close as desireable. And, as always, when preaching without notes, mistakes are made. Dvorak was Czech for example, not Hungarian. But as I remarked in the sermon following the great African theologian St. Augustine, our mistakes are only another way for the one we call our Higher Power to show that power even in our weakness.)

In my new job as an addiction recovery chaplain, one of the first themes we have explored in chapel was that of the need for trust. For reasons that I think will need a book to work out, my own thoughts on this topic draw me continually to the subject of birds, in particular, sandhill cranes. This is a snippet of some draft notes for that book.

Most of my friends know by now of my deep and passionate love of a pair of sandhill cranes that reside in a marsh here in Medina County. I named them Gene and Grace (Kelly) for a number of reasons. Cranes are renowned for their remarkable dancing and for me the image of Gene Kelly dancing in the rain is one that fills me with great joy, especially knowing that he had a high fever on the day he shot that iconic dance scene. Also, one of my best friends in college, one who listened with amazing attentiveness to me as I struggled with my own wounds is also named Eugene, or Gene as we called him then. Naming animals is a tricky thing, but usually they have a way of letting you know if you’ve got it right.

Gene dancing up a storm

Grace lost the bottom part of her leg this spring in an accident and now relies even more upon her partner Gene to keep watch for her and the potential enemies she is less able to defend herself from. As I watched her bow down low on one leg to forage for food, I was struck by the gracefulness of her movements and the name Grace seems most fitting as I thought of the slow moving beauty and resilient strength of the iconic Grace Kelly.

Grace preening on one leg. How could she not be Grace?

Cranes are the oldest species of bird known. They have been revered by all cultures, civilizations, and religious traditions where they reside, including the Buddhist, native American, African, and Christian traditions.

Cranes typically mate for life and are fiercely loyal to one another. Both the male and female take time to sit on the nest while the other keeps guard and gets some food. Because Grace lost part of her leg this spring, they were unable to produce any offspring. Grace struggles somewhat to forage, and when she does, she is more vulnerable since she can’t use one of the bird’s best defenses, a strong kick. Gene is always by her side. Always. And when she bends down to eat, he is usually scanning the horizon for any threats. This is trustworthy love in action. We are all wounded in ways, but some are more vulnerable than others and one way to think of prayer or spiritual practice is as attentiveness to the vulnerable heart of another. This is Gene in action.

Gene on the lookout while Grace gets a breakfast of soybeans in a field near their marsh home

In the Christian tradition cranes are revered for their prayerful attentiveness. It was believed that, like monks in a monastery, or residential staff in a recovery center, it was crucial for there to be one or two cranes who stayed awake all night to insure the safety of the rest. Cranes are known for sleeping on one leg. In the medieval imagination, it was believed that the other leg held a large rock, symbolizing the rock of Christ, which, if the guardian bird were to accidentally fall asleep, would hit the ground with a loud thud and awaken the birds to their danger. These verses from the First Epistle of Peter were likely in the monks minds when the imagined the cranes this way:

Cast all your anxiety on him, because he cares for you. Be sober. Be Watchful. Your adversary the devil prowls around like a roaring lion, seeking someone to devour. Resist him, steadfast in your faith, for you know that your brothers and sisters in all the world are undergoing the same kinds of suffering.

Here are snippets from two sermons speaking of their qualities and an icon from a medieval Christian bestiary. Theologian birdwatchers have been drawn to their watchfulness, one of the most important qualities in a strong prayer life. Though their ornithological accuracy may be in doubt in the thoughts, Isidore and St. Antony are surely on to something by seeing that our own attentiveness to the virtues of natural world have much to teach us. By their faithful presence to one another day after day, Gene and Grace have taught me a great deal about how to be a trustworthy partner to those I love. And they have taught me one way to think about what it means to pray without ceasing.

Isidore of Seville [7th century CE] (Etymologies, Book 12, 7:14-15): Cranes (grues) take their name from the murmuring sound they make. When they are travelling somewhere they follow the letters of the alphabet. They fly at great altitude so they can see the lands they seek. The leader in flight maintains the line of birds with its voice; when it grows hoarse another bird takes its place. At night they take turns acting as guard; the one on duty holds a small stone in its claws to hold off sleep, and cries out at anything to be feared. Their age is revealed by their color, because the darken as they grow old.

St Antony of Padua [12th-13th century CE] (Sermons): Merciful men compared to cranes. Let us, therefore, be merciful, and imitate the cranes, who, when they set off for their appointed place, fly up to some lofty eminence, in order that they may obtain a view of the lands which they are going to pass. The leader of the band goes before them, chastises those that fly too slowly, and keeps together the troop by his cry. As soon as he becomes hoarse, another takes his place; and all have the same care for those that are weary; so that if any one is unable to fly, the rest gather together, and bear him up till he recovers his strength. Nor do they take less care of each other when they are on the ground. They divide the night into watches, so that there may be a diligent care over all. Those that watch hold a weight in one of their claws, so that, if they happen to sleep, it falls on the ground and makes a noise, and thus convicts them of somnolency. Let us, therefore, be merciful as the cranes; that, placing ourselves on a lofty watch-tower in this life, we may look out both for ourselves and for others, may lead those that are ignorant of the way, and may chastise the slothful and negligent by our exhortations. Let us succeed alternately to labour. Let us carry the weak and infirm, that they faint not in the way. In the watches of the night, let us keep vigil to the Lord, by prayer and contemplation.

Sudden Illumination

This post continues a line from my previous post about seeing the foundation of the Christian community as an act of artistic vision and commitment.

Gurdon Brewster’s Jesus and Buddha dancing ecstatically. Are you sure you can tell who is who? St Peter would be proud I think!

We are treated as impostors, and yet are true

(2 Corinthians 6:8).

I will always associate this verse from Paul with Reinhold Niebuhr’s remarkable sermon from his book Beyond Tragedy which I read while at the University of Chicago Divinity School in the mid 1990’s.

Niebuhr really stretched out in his sermon, reading this verse as a way of thinking of the art of storytelling, myth, legend and poetry as privileged means of theological exploration. i.e. myths are sometimes seen as ‘impostors’ because they aren’t ‘literally’ true, and yet, as Niebuhr passionately argued, our stories as much as our dramatic, poetic leaps of body and spirit are often the closest we can get to articulating the mysterious truth of God’s presence in our lives.

It was, I realized only much later, a rather brilliant rejoinder to Plato’s dismissal of the artists from his ideal polis, Niebuhr suggesting that there was more “truth in myths” (which I think was the title of the chapter in Beyond Tragedy) than there was in the desiccated reasoning of the literalizers.

Speaking of Niebuhr, I can’t wait for the chance to head to NYC, to visit the library of Union Theological Seminary, Niebuhr’s stomping grounds for most of his theological career. There I believe still sits the bust of Niebuhr made by our beloved Gurdon Brewster, who shared with me the story about how Niebuhr growled at him when Gurdon asked to do his bust. “Don’t do it in bronze, I’m not dead yet!” was his response, and then he insisted he was too busy to sit for Gurdon to study and cast him. Classic Niebuhr gesture, who once told Paul Tillich to hurry up on one of their daily theological talk/strolls because Tillich was too busy smelling the flowers. “They’ll still be there tomorrow!” Niebuhr impatiently reprimanded. Score one for Tillich in their ongoing theological debate. Stopping to smell the flowers while on a walk is always good-better-best theological practice!

Gurdon accepted the challenge, by the way, and gathered as many photographs of Niebuhr as he could to do the painstaking work of casting Niebuhr’s bust while the man himself continued to fly about his work with barely a pause to catch his breath. Is the bust an accurate representation of the man? Given that he never stood still, a bust of Niebuhr is in and of itself a bit comical, but I can’t wait to give it a look. Niebuhr was for many years my theological hero and it when Gurdon dropped his name during my first conversation with him over lunch in 2008, I knew I’d made a friend worth his weight in bronze or gold.

Gurdon Brewster, imposter, yet true…thank you my dear friend!

Though the artist must be willing to enter into the crux of human suffering, anxiety, and the propensity for violence against both self and other, the artistic spark comes from a deeper place.

Here is Juan Diego responding to Our Lady of Guadalupe’s visitation to him even as he struggles with his own deep sense of loss from the ravages of colonialist violence:

“Then he dared to go to where he was being called. His heart was in no way disturbed, and in no way did he experience any fear; on the contrary, he felt very good, very happy…The mesquites, the cacti, and the weeds that were all around appeared like feathers of the quetzal, and the stems looked like turquoise; the branches, the foliage, and even the thorns sparkled like gold. He bowed before her, heard her thought and word, which were exceedingly re-creative, very ennobling, alluring, producing love.”

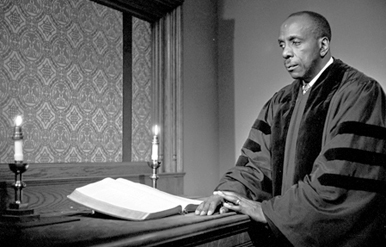

Here I am reminded of one of Gurdon‘s last sculptures, the overpowering Prophetic Thunder. I remember him telling me about how tired he was of images of King that sanitized his prophetic fire.

And I imagine that in order to articulate this fire into bronze, he must have had to discipline himself with exquisite attentiveness: returning again and again to this ‘re-creative, very ennobling, alluring…love,” in order not to go astray into bitterness and resentment as he worked. This spiritual discipline of the artist is deeply analogous to what King had to do day after day as he faced the violence of American racism and economic and political inequality. Art, spirituality, and social justice are intimately related in this tradition Gurdon brought to Cornell and shared for so many years.

In this inspired sculpture, currently on display at the Tompkins County Public Library, we see that in Gurdon’s time with Daddy King and the beloved community, he learned his lessons well.

20160115GH GURDON BREWSTER Sculptor Martin Luther King Jr. Sculpture